Ethereum Is A Security: Is It A Controversial Absurdity From The SEC’s Tightening Policy?

The article first introduces the U.S. “Securities Act,” and the Howey test, then explains the misunderstanding that Ethereum is a “security”, and focuses on demonstrating that POS cannot meet the two conditions of “common cause” and “other people’s efforts” in the Howey test. Therefore, ETH Solo Staking will not constitute an investment contract, so it is not a securities transaction.

Background introduction

After Ethereum shifted from the proof-of-work( PoW) consensus mechanism to the proof-of-stake (PoS) consensus mechanism, some people, including SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, believe that Ethereum’s new equity model may lead to ETH being regulated by the US Securities Act are considered “securities.” The reasons are:

(1) POS validators need to lock 32 ETH for “investment”;

(2) participate in the “common cause” composed of various validators;

(3) have profit expectations from obtaining staking rewards;

(4) profit Efforts from other validators or other parties involved in the validation process.

Leaving aside whether the verifier’s deposit of ETH into the smart contract is in line with “money investment,” the behavior of ETH or staked ETH is regarded as an “investment contract” because it cannot satisfy the second point (common cause) and the fourth point of the Howey test (other people’s efforts) and cannot be established. In addition, no one on Ethereum has privileged access to information that may need to be disclosed to the public.

These arguments stretch the interpretation of the Howey test beyond recognition and fail to recognize fundamentally that the fundamental purpose of the Securities Act is to address information asymmetries in any situation. The following analysis demonstrates that the transformation of Ethereum to POS does not make ETH or ETH staking behavior constitute an “investment contract”; otherwise, it will lead to the absurd application of the Securities Law.

The U.S. Securities Act and the Howey Test

The U.S. Securities Act requires issuers to apply for registration with the SEC for any issuance or sale of “securities” unless an exemption is obtained. Registration requires issuers to enforce disclosure, ensures that important information is shared with investors to make informed decisions, prevents any form of information asymmetry, and avoids agency problems.

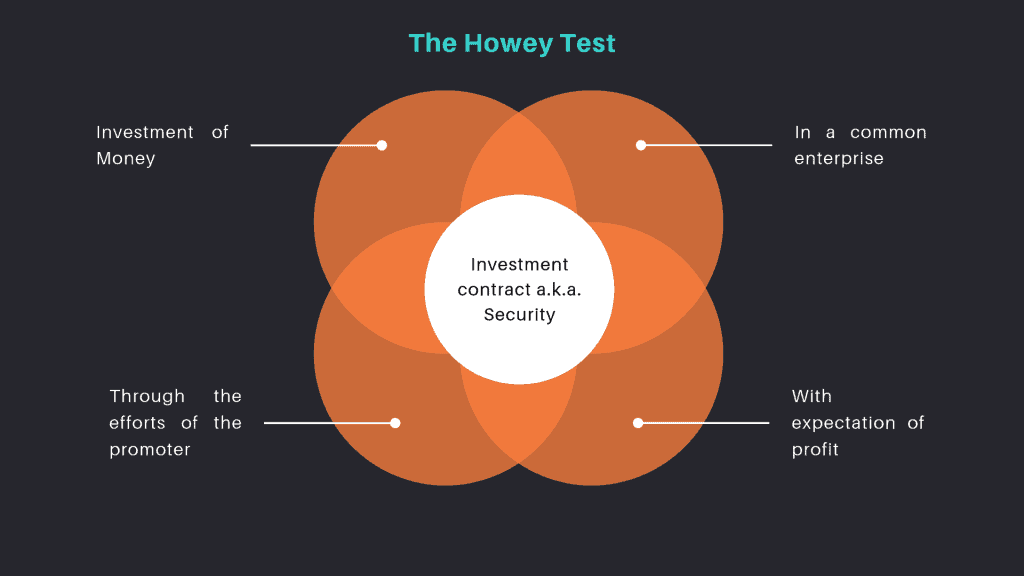

The Securities Act of 1933 enumerated types of “securities,” which included “investment contracts.” As the Supreme Court pioneered in Howey, an “investment contract” consists of:

(1) an investment of money;

(2) a common enterprise;

(3) a reasonable expectation of profit;

(4) effort.

To meet this definition, a contract, plan, or transaction must satisfy all four dimensions. The court adopts a flexible approach to interpreting the “investment contract”, focusing on the “economic reality” between the promoter and the investor. In many cases, courts have adopted an “economic reality” interpretation to limit the scope of “investment contracts” and the application of the Securities Act.

POS cannot meet the condition of “common cause” in the Howey test

Legal Basis

As stated by the Supreme Court in Howey, an important condition of what constitutes an “investment contract” is a “common cause.” While some courts have held that a “common cause” exists only if a “horizontal commonality” is met, others have held that the existence of a “vertical commonality” is sufficient to qualify as a “common cause” in the Howey test.

According to the following analysis, ETH staking has neither “horizontal commonality” nor “vertical commonality,” so it cannot meet the conditions of “common cause” under the Howey test.

There is no “horizontal commonality” between POS validators

“Horizontal commonality” occurs when investors are linked to other investors by committing their funds to a pool (often agreeing to share profits proportionally). The promoters need to commingle investors’ funds and use them for a common cause.

In other words, the court emphasized that “horizontal commonality” requires tying the expected profits of individual investors with other investors “through the entrepreneurial efforts of the promoters,” requiring investors to give up any personal claim to profits in exchange for sponsorship. Individuals enjoy proportional distribution rights in the subsequent distribution of profits.

Some views mistakenly believe that there is “horizontal commonality” in ETH staking because validators deposit ETH into a single smart contract address (a so-called pool) or that there is some kind of cooperation between validators. Through the following analysis, it can be seen that these views are all misunderstandings of the ETH staking mechanism.

First, to become a validator on the Ethereum network, 32 ETH needs to be deposited into a smart contract address (called a “deposit contract”). However, depositing ETH into a deposit contract is not depositing into a pool, as the Ethereum network will never be controlled by a single person.

On the contrary, the purpose of ETH staking is to create an incentive mechanism to ensure the operation of the Ethereum network: it first needs to ensure that the validator has a certain interest in the network so as to prevent being punished for doing evil. Additionally, although each validator’s ETH is deposited in the deposit contract, it is not commingled and can still be distinguished, and after the network upgrade, each validator will be able to get back their staked ETH.

Individual validators also do not have the right to participate in a pro-rata share of the common cause’s profits. Rewards vary from validator to validator, depending primarily on the individual efforts of each validator; validator input does not rise or fall based on the success or failure of any promoter’s entrepreneurial endeavors. Therefore, courts should find a lack of “horizontal commonality” when analyzing the economic realities of ETH collateral.

There is no “vertical commonality” among POS validators

Some courts hold that the condition of “common cause” in the Howey test can also be satisfied through “vertical commonality,” which focuses on the relationship between the promoter and the investor, requiring that the wealth of the two be closely linked. However, since the Ethereum network has no initiator, there is no “vertical commonality.”

Generally speaking, the smooth operation of the Ethereum network does not depend on any key party; it is “fully decentralized.” To ensure decentralization, Ethereum’s consensus mechanism allows validators to operate independently without relying on any third party. Validators can freely and voluntarily join the Ethereum network or withdraw at their own discretion.

Validators can play their roles according to the rules of the Ethereum network without relying on others, and validators will be rewarded according to these rules, not according to the efforts of the initiators. An in-depth analysis of the economic realities of ETH staking reveals that there are no originators that validators need to rely on.

POS does not meet the “effort of others” condition in the Howey test

Legal basis

According to the statement of the Supreme Court in the Howey case, one of the conditions constituting an “investment contract” is that the investor expects profits only from the efforts of the promoter or a third party (solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party).

The appellate court downplayed the “only” (solely) test and focused instead on whether the promoter’s efforts were undeniably significant to the success of the cause. According to the SEC’s guidance, these efforts are summarized as: affecting the success of a business or career through the application of professional skills and decision-making abilities.

Contrary to the SEC, the court focuses on whether the investor has the ability to control the profitability of his own investment. The greater the degree to which an investor can control the earning power of an investment through his own efforts, the lower the probability that the transaction will be characterized as an “investment contract.”

In such a case, since the investor may have control over the common venture separate from the sponsor’s ownership, the application of the Securities Act or disclosure requirements to the sponsor would not be necessary. The court further outlined the following factors (Schaden test) to test an investor’s “ability to control”:

(1) the investor’s access to information;

(2) the investor’s contractual powers;

(3) the investor’s contribution of time and effort;

(4) the adequacy of financing;

(5) the nature of business risk; and

(6) the degree of speculation.

Some views believe that Ethereum’s transition from proof of work to proof of equity is a transition from a competition mechanism to a cooperative mechanism because the verification process in proof of equity requires the participation of multiple parties. According to this view, when staking ETH, each validator can reasonably expect to rely on the efforts of other validators to earn staking rewards.

This view misunderstands the Ethereum POS validator rewards mechanism and reduces the standard of “completely relying on others’ efforts” in the Howey test to an unprecedented degree. As explained below, Ethereum validators are less cooperative in POS than in POW, and validators are mainly rewarded for their own efforts and funds. For this, it is helpful to understand how validators are rewarded in Ethereum POS.

Reward mechanism for verifiers under POS

Many factors go into calculating validator rewards. Under the POS mechanism, verifiers will receive rewards every epoch (6.4 minutes), and these rewards are calculated as a multiple of the “base reward.”

The base reward Solo is determined by the number of active validators on the network (total active stake) and is dynamically adjusted to incentivize the required size of the validator set. The total amount of staking stake in the network is arguably the most influential factor in determining rewards for validating exchanges.

Verifiers can get rewards in the following ways:

(1) correct source;

(2) correct target;

(3) correct block header; these 3 kinds of verification (voting) (collectively referred to as “accurate reward” accuracy rewards); and

(4) include their validation (voting) in a block (“inclusion reward”). Inclusion rewards are split among randomly selected validators and validators for producing a block.

According to the researchers, assuming a fixed base reward over time, a single validator’s profit is largely determined by the validator’s ETH balance deposited in the network, capped at 32 ETH. The higher the verified balance, the greater the rewards and penalties, and vice versa. A significant portion of the validation reward will also depend on the chances of a validator randomly receiving a proposed block within a limited time frame.

Validators profit from their own efforts, not from others

By analyzing the economic reality of ETH staking, the court should find that it does not qualify as “efforts of others” in the Howey test. Rewards for staking are primarily determined by the personal efforts of validators, without relying on any administrative efforts by third parties. As mentioned above, validators’ rewards are largely determined by the amount of ETH they stake and the random chance they receive to propose a block, both of which are based on individual efforts and do not depend on any third party.

In other words, validators retain their ability to control investment returns. Using the Schaden test, there is no information asymmetry in the control of the verifier; the reward is based on an open-source protocol, and the distribution is recorded on the public blockchain. Rewards also depend on the time and effort contributed by validators since validators must maximize their connection to the network.

While other validators are sometimes incentivized to join the network (when the base reward increases), their ability to earn rewards depends on the participation and actions of other validators (such as public verification broadcasts), but the validator never depends on any “entrepreneurial” or “managerial” endeavors required in the Howey test.

Conclusion – Ethereum is not a security, ETH Solo Staking does not constitute an investment contract

To sum up, by analyzing the economic reality of the Ethereum POS pledge, the court should find that the ETH pledge does not satisfy the Howey test because there is no “common cause,” and the verifier does not rely on “other people’s efforts” to get rewards. Similarly, whether depositing ETH into an Ethereum address qualifies as a “money investment.” Therefore, if any of the four items of the Howey test are not satisfied, the transaction does not constitute an investment contract and therefore is not a transaction in securities.

Leaving legal analysis aside, it would be ridiculous if we applied the strict requirements of the U.S. Securities Act to ETH staking. As noted earlier, one purpose of securities regulation is to improve the information asymmetry that exists between promoters and investors through disclosure. Therefore, if ETH staking is considered an “investment contract,” then a disclosure obligation would be imposed on the originator.

As analyzed above, when a validator deposits ETH as collateral, there is no identifiable originator. But if we fulfill the disclosure requirements of the Securities Act and let the verifier become the role of “sponsor” or “issuer,” then it is very unreasonable for the verifier to fulfill the obligations of securities registration, periodic reporting, and disclosure requirements.

Does the Securities Act require verifiers to provide relevant disclosures? What important information do validators need to disclose? How will this help resolve any information asymmetries, and how will it serve the public interest? Answering these unrealistic questions illustrates just how deeply flawed the logic of applying the Securities Act to validators on the Ethereum network is: they do not present the risks that disclosure is intended to address.

DISCLAIMER: The Information on this website is provided as general market commentary and does not constitute investment advice. We encourage you to do your research before investing.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  USDC

USDC  TRON

TRON  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  Cardano

Cardano  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Chainlink

Chainlink  Monero

Monero  LEO Token

LEO Token  Zcash

Zcash  Stellar

Stellar  Litecoin

Litecoin  Hedera

Hedera  Dai

Dai  Cronos

Cronos  Tether Gold

Tether Gold  OKB

OKB  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  KuCoin

KuCoin  Gate

Gate  Algorand

Algorand  Cosmos Hub

Cosmos Hub  VeChain

VeChain  Dash

Dash  Tezos

Tezos  TrueUSD

TrueUSD  Stacks

Stacks  IOTA

IOTA  Basic Attention

Basic Attention  Theta Network

Theta Network  Decred

Decred  NEO

NEO  Synthetix

Synthetix  Qtum

Qtum  Ravencoin

Ravencoin  DigiByte

DigiByte  0x Protocol

0x Protocol  Nano

Nano  Zilliqa

Zilliqa  Holo

Holo  Siacoin

Siacoin  Numeraire

Numeraire  Waves

Waves  Status

Status  BUSD

BUSD  Enjin Coin

Enjin Coin  Pax Dollar

Pax Dollar  Ontology

Ontology  Hive

Hive  Lisk

Lisk  Steem

Steem  Huobi

Huobi  NEM

NEM  OMG Network

OMG Network  Bitcoin Gold

Bitcoin Gold  Augur

Augur  Ren

Ren  HUSD

HUSD